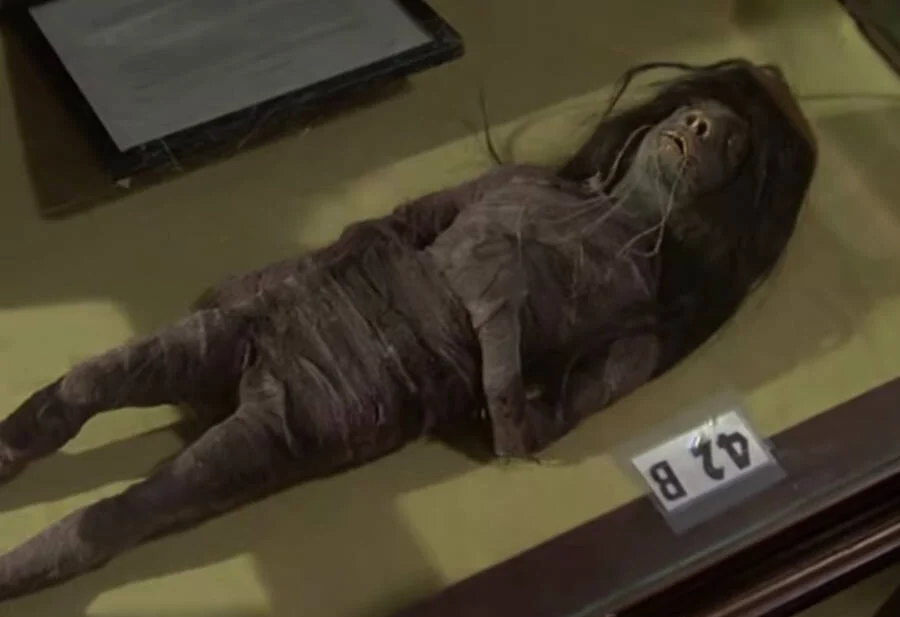

Almost 100 years ago in the Ecuadorian Amazon, a warrior died at the hands of an enemy. His head was cut off, boiled, and shrunk into a war trophy. After being traded to an American, the shrunken head was brought to Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. There, it was put on display, used as a film prop, and eventually locked into storage.

But after a careful authentication process, the shrunken head — called a tsantsa — was finally sent home in 2019. An article published in May in Heritage Science has documented that process for the first time.

“This is not an oddity — this is somebody’s body, this is somebody’s culture, and it’s not ours,” said Mercer University chemist Adam Kiefer, one of the article’s co-authors.

“So from our perspective, repatriation was essential, and we were very lucky that our university supported this endeavor.”

Mercer University biologist Craig Byron used a 33-point checklist to authenticate the shrunken head.

After years in storage, the head was first rediscovered by Keifer’s co-author, a Mercer biologist named Craig Byron. Byron, overseeing the transfer of various taxidermy specimens to a new science building, realized that the Ecuadorian shrunken head needed a second look.

Byron and his colleagues didn’t know much about the head, but started piecing its story together. Measuring about five inches high, the head had bounced between different university museum displays until the 1980s.

In the late 1970s, the university loaned it to director John Huston to use as a prop in his 1979 comedy Wise Blood, based on the Flannery O’Connor novel. O’Connor had lived near Macon, and the movie was filmed nearby.

The Mercer scientists also determined the head had come from Ecuador. An Army Air Force officer named James Harrison had collected it in 1942, long before the establishment of regulations meant to stop the trafficking of cultural artifacts and human remains.

“It was Indiana Jones,” Kiefer said. “When this was collected, science was different, everything was new… but almost 80 years later, we recognize its cultural importance, along with the science.”

YouTubeThe shrunken head was used as a prop in the film Wise Blood.

Tsantsas were created from the severed heads of vanquished foes. Victors removed the skull, brain, and facial muscles before sewing the eyes and lips shut. They then molded the skin as it dried and shrunk. These war trophies were meant to trap the spirit of the enemy and give power to his killer.

“Anyway, they had two shrunken human heads,” Harrison, who later became a biology professor at Mercer University, wrote in his memoirs. “I badly wanted one of those heads and by motions and gestures got the idea across.”

He traded some coins, a pocket knife, and a military insignia for the tsantsa.

Eighty years later, scientists at Mercer University reached out to Ecuadorian officials for guidance on what to do. After contacting the Ecuadorian Embassy, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, and the National Cultural Heritage Institute, the Mercer scientists agreed to first authenticate the artifact.

Doing so was easier said than done. Europeans had developed a fascination for the tsantsa in the 1850s. As a result, people in the Amazon produced shrunken heads without any ceremonial value.

Heritage Science The scientists had to make sure that the head met dozens of different criteria.

So, Byron and Keifer used a checklist of 33 criteria to determine the shrunken head’s authenticity. They studied skin attributes like color, density, and texture as well as the structure of the facial features. They also looked for signs of traditional fabrication like traces of charcoal in the head cavity and a hole at the top of the head for attaching a cord.

By the end of their study, they were satisfied that they had an authentic tsantsa.

“Most checklist indicators of authenticity (30/33) affirm that the Mercer tsantsa is ceremonial,” their paper explained.

In addition to evidence like head lice, the scientists also found marks in the skin left by the person who had first made the tsantsa.

“You can even see where fingers and thumbs would have been used to hold and ‘work’ the skin during the shrinking process,” Byron said.

After they authenticated the tsantsa, Ecuador agreed to take the artifact back. But the Mercer scientists aren’t sure what happened to the shrunken head after that.

“It’s not our decision to make, where this cultural artifact ends up,” said Kiefer. “Our job was to make sure that it was reunited with people who know more about the culture and the context, to make the appropriate decision on how to display this.”