Kate Warne was so good at her job that barely anyone knows her name today.

The Pinkerton’s logo, which is credited with first inspiring the term “private eye.”

Kate Warne wasn’t necessarily beautiful, so she didn’t draw unwanted attention. She had an expressive and honest face that made people want to tell her their secrets. She was thin and moved with graceful self-assurance.

Warne was, in other words, perfect for detective work. The only problem was, she was a she.

Seeing a woman in the Pinkerton detective agency offices in 1856, Allan Pinkerton assumed that Kate Warne was looking for a secretary job.

No, the young widow corrected him. She was actually responding to an ad that he had placed in a local Chicago newspaper looking for a new detective.

“At the time, such a concept was almost unheard of,” the Pinkerton company records say.

“It is not the custom to employ women detectives,” Pinkerton warily told the 23-year-old.

Warne asked him to hear her out. A woman, she said, could be helpful for “worming out secrets in many places which would be impossible for a male detective.” She could make friends with the wives and girlfriends of suspects and eavesdrop on unsuspecting men, who tend to brag when ladies are around.

Pinkerton brought her on, and Warne quickly proved those theories right.

Chicago History MuseumA watercolor of Kate Warne from 1866. There are no known photos of the elusive detective.

In 1858, for example, Warne gained the confidence of Mrs. Maroney, whose husband had stolen $50,000 from the Adams Express Company equity fund. From her chats with the wife, Warne gathered a good deal of the evidence needed to convict Mr. Maroney, who returned more than $30,000 of the stolen cash and was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Impressive enough in its own right, that task seems almost trivial when compared to Warne’s next assignment: protect President-elect Abraham Lincoln from assassination.

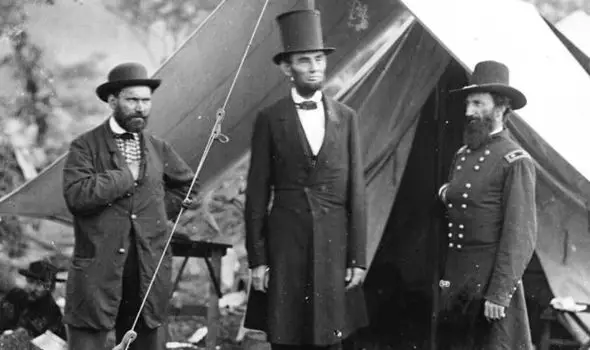

Library of CongressAllan Pinkerton (far left) stands next to President Lincoln at the Battle of Antietam on October 3, 1862. Kate Warne had accompanied Pinkerton on this trip to meet with an Ohio Division of the Union army.

It was 1861 and the agency had been hired to look into secessionist activity and threats on the Maryland railroad. Pinkerton and his team realized that the risks stretched well beyond trains — with Lincoln himself as the ultimate target.

The organization deployed five agents to Baltimore, including Warne. Adopting a thick southern accent, the New York native transformed into Mrs. Cherry or Mrs. M. Barley, a rich and flirtatious southern lady in town to socialize at classy secessionist gatherings.

The plan, the partygoers told Mrs. Cherry, was to kill Lincoln on his way to Washington D.C. for the inauguration.

At the train stop in Baltimore, they knew he’d have to transfer to another rail system a mile away, and would pass through the station’s lobby to get to his carriage.

It was then that the assassins planned to strike, breaking out in a fight to distract Lincoln’s security and then surrounding him with a murderous mob. A boat had already been chartered for their getaway.

Upon hearing these details, Warne would laugh and exchange pleasantries in order to maintain her cover before soon reporting back to Pinkerton.

Pinkerton then went about delivering the information — which other detectives had pieced together and corroborated as well — to Lincoln, who was hesitant to pay the threat any mind.

Eventually, though, they convinced him that he must take caution, and thus they established a plan to deliver him safely to the White House. Warne organized most of it.

“She handled securing the last car on the train so they could get him easily on and off,” Kate Hannigan, who wrote a fictional book based on Warne’s story, told the Chicago Tribune.

“They disguised Lincoln as her invalid brother. They made him stooped and with a cane and threw a big coat over him. There were two detectives on the train with him, Allan Pinkerton and Kate Warne. So she played a big role.”

She accompanied the 16th president on most of his journey — reportedly not sleeping for one second all night. Though the president would be mocked for this seeming act of cowardice for the remainder of his time in office, he arrived safely to take the oath of office.

Harper’s Weekly“Flight of Abraham”, Harper’s Weekly, March 9, 1861

Pinkerton grew to rely on Warne, who took on many roles in her spy career.

She’d pose as Pinkerton’s wife while collecting crucial military intelligence for Major George McClellan throughout the Civil War. She became Mrs. Potter, who coaxed a confession out of a murderer’s wife in Mississippi. She became Lucille, a fortune teller who unveiled a plot to poison a man named Captain Sumner. She became Kay, Kitty and Angie — so many names that historians are unsure which actually belonged to her.

Most notably, she became the head of a new branch of female detectives.

“In my service, you will serve your country better than on the field,” Pinkerton reportedly told his prospective hires. “I have several female operatives. If you agree to come aboard you will go in training with the head of my female detectives, Kate Warne. She has never let me down.”

In 1868, Warne died of pneumonia at the age of 38. Pinkerton was by her side and she was buried in his family’s cemetery plot, right alongside several other Pinkerton agents.

No known pictures of Kate Warne survive, and her name — misspelled with no “e” — is slowly fading from her headstone. “Here’s this incredible woman in history who has been dismissed,” Hannigan bemoaned. “She’s not even a footnote in history.”

But is that an unfair omission, or simply the sign of a really good detective? Isn’t it possible that the name “Warne, Kate Warne,” doesn’t ring a bell precisely because she didn’t want it to?

She was, after all, one of the best in the business.